Tokyo Mental Health is here to support you and provide you with the help you need.

What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)? How did it come about?

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a form of “third wave” behavioral therapy. The “first wave” was characterized by behaviorism pioneered by psychologists such as John B. Watson, Ivan Pavlov and B. F. Skinner. Classical conditioning and operant conditioning, defined by the behaviorists, are examples of learning processes based on associations made between behavior and consequence. Classical conditioning is a process whereby an unconditioned stimulus, which evokes an unconditioned response, is paired with a neutral stimulus, referred to as the conditioned stimulus. The neutral stimulus alone then evokes the same unconditioned response as though there is a relation between the two previously unrelated occurrences.

The “second wave” of behavioral therapies such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) and Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), developed by Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis respectively, integrated thoughts and beliefs into a new understanding of changing behavior and emotional experiences, following the “cognitive revolution” that superseded Skinner’s “radical behaviorism.”

The “third wave”, a term in use since 2004 (Hayes, 2004), refers to emerging approaches to behavioral therapy focusing more on how the individual relates to the functions of their internal experiences, as opposed to the “discover & eliminate” approach in previous iterations of behavioral therapies. Here several concepts such as mindfulness, spirituality, values, psychological flexibility and acceptance are incorporated into psychological interventions and extend existing behavioral therapy techniques.

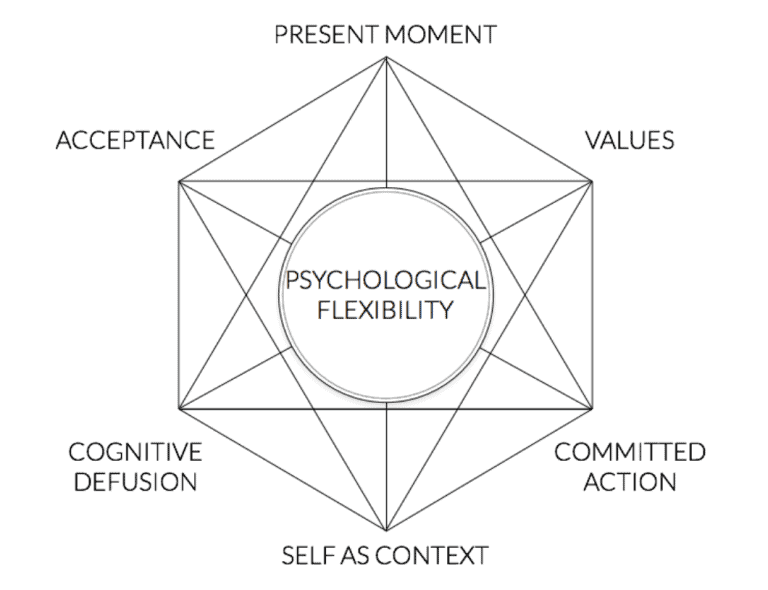

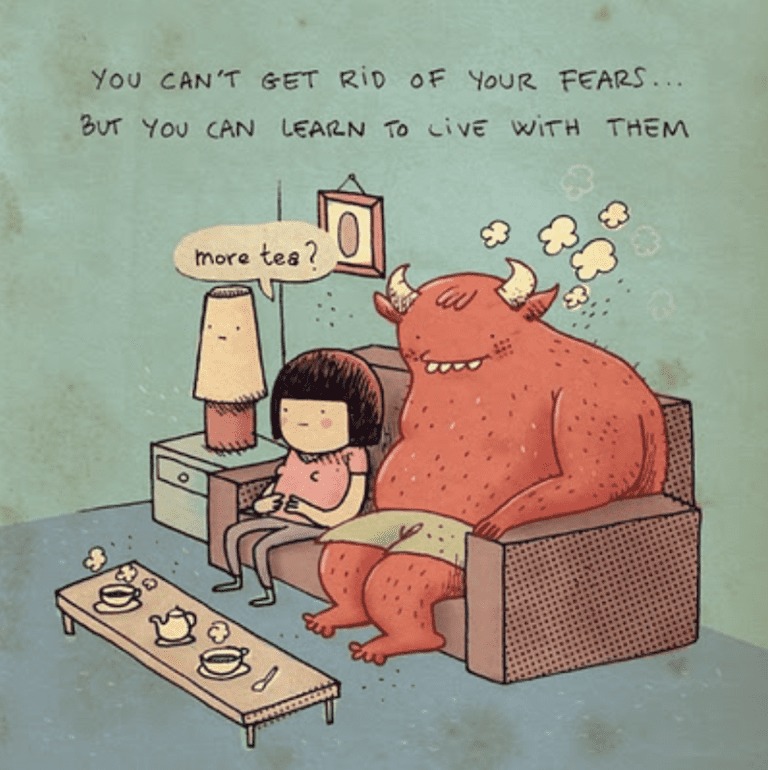

ACT itself is based on the concepts of mindfulness, acceptance and values. ACT posits that the experience of living with psychological pain is normal, and that attempts to eradicate pain only leads to more pain. The mind is naturally inclined to adopt eradicating and problem solving techniques. While this works in many domains of life, the “fix-it” mentality fails to bring resolution to psychological pain. Instead, ACT encourages being mindful and viewing your pain as a normal state of being which does not define you. Psychological pain exists alongside living the life you value, and the first step towards alleviating suffering is acceptance of that pain. ACT promotes having psychological flexibility in viewing your pain, broadening your repertoire of responses and letting go of being entangled in your struggle (Hayes & Smith, 2005). The goal ultimately is to achieve greater psychological flexibility.

What are the central concepts or themes in ACT?

Acceptance

The goal of acceptance in ACT is not about feeling better, but about how to “feel better,” be it a positive feeling, a negative feeling, or any feeling in between. It is about actively and willingly allowing experiences to occur, much like you would experience rhythm in music or texture in cloth. The goal of acceptance is to open yourself to the vitality of the moment, and then to be able to move effectively towards your values. Acceptance is based on the notion that applying the “fix-it” technique to internal experiences (otherwise known as experiential avoidance) only entangles you further into the experience.

Values

A values based life is one that you wish to live according to the qualities and ideals that you believe in, that bring you fulfillment when you practice or work towards them. Often we put this life aside thinking that in order to achieve the life that one wants, one must first overcome one’s pain. ACT posits that you can live the life you want right now, and that pain is a normal part of our lives. Psychological pain has a history, and with the unfortunate nature of relational thinking, will continue to exist. In that regard, it is impossible to completely eradicate past experiences. Psychological pain is no barrier to living a values-based life more than our own thoughts making it one.

Being Present/Mindfulness

Mindfulness is not a technique to distract yourself from your experiences. It is about actively being aware of your experiences without evaluation, judgment, fusion, defense and with a sense of acceptance. Our internal struggle often produce expressions such as, “I am anxious”, “I am failure” or “I am worried. This experience is a combination of memories, sensations, thoughts and emotions that you remember, sense, think and feel instead of being a definition of you. We often get wrapped up in a vicious cycle of thoughts and feelings in trying to make sense of it, finding a solution or in attempting to “fix-it”. Being aware that this is merely an experience along with noticing the verbal rules and relational frames that occur is what makes up mindfulness. A starting point to mindfulness can be to practice being in the moment i.e., notice your 5 senses as they are seeing, touching, hearing, tasting and smelling in the moment.

Cognitive Defusion

The goal of cognitive defusion is to break free from the illusion of language and to notice the process of thinking. It is common for humans to relationally fuse experiences such that the relationship between experiences can be reversed without direct experience. A traumatic experience that causes anxiety is a direct experience. Feeling anxious and triggering the memory of the traumatic experience is an example of a thought derived relational fusion. As more experiences become fused, they become anxiety provoking. Cognitive defusion encourages you to notice that such linguistic illusions only occur when you think about them. Imagine having both your palms on your face. You wouldn’t be able to see much, and as you move your palms further away, you notice more and more of your palms. Likewise seeing your thoughts as they are, “just thoughts” requires getting some distance from your thoughts. Adding the phrases, “I notice” or “I am thinking” prior to your thoughts and feelings creates that distance and a reduced sense of fusion towards them. For example, “I notice that I am thinking that I am anxious” or “I notice I am feeling worried” is similar to “I am looking at a tree” such that you do not suddenly become the tree.

Self as Context

In ACT, there are three senses of self; the conceptualized self (e.g., “I am kind”, “ I am anxious”), the “self as an ongoing process of self-awareness”, and the “observing self”. The “self as an ongoing process of self awareness” refers to a flexible and in the moment process of awareness such as “I am seeing the mountain”, “I am feeling upset” or “I am thinking about having dinner”. The observing self is the idea that you are not your thoughts, feelings and emotions but instead you are merely experiencing them, much like the other thoughts that come to mind. Self as context is related to the observing self, the ‘place’ from which you observe and experience cognitions. Self-debilitating thoughts, judgment and evaluations of self often result when we believe our thoughts as being a reflection of ourselves. One might think, “I made a mistake, I am a failure” when actually, your observing self is experiencing it as a thought. As such, the experience could be expressed more like, “I notice I am thinking that I made a mistake and also the thought that I am a failure”.

The Chess Metaphor is an example of viewing self as context. A chess board consists of pieces of contrasting colors. Imagine the pieces on the chess board being experiences such as thoughts, emotions, cognitions, memories, or sensations. At one end there are pleasant experiences (white pieces) and on the other, unpleasant and distressing ones (black pieces). The game between these pieces represents the internal struggle, and we become invested in winning the battle between the “good” and “bad” pieces on the board. We are hoping to overcome the “bad” with the “good”. This method is challenging because firstly, for every “good” piece brought forward, a “bad” piece is attracted. For example “I am a good partner” attracts, “No you are not, what about the time you said that” or “I accept myself” attracts, “No you don’t, what about your (insert imperfect feature)”. Secondly, there are an endless number of positive and negative experiences and the battle goes on indefinitely.

Rather than “you” being the pieces or players, your observing self in this metaphor is said to be the chessboard, a space which is constantly in contact with the pieces that you are experiencing, yet not directly involved in the battle.

Committed Action

Committed action in ACT is a values driven process of achieving behavior change goals. Think of it as short term, medium term and long term action steps that are consistent with the values you hold. Committed action is the final step of ACT while the other processes mentioned above work on psychological barriers inhibiting you from living a values driven life. The goal ultimately is to obtain higher psychological flexibility.

If you are interested in ACT and would like to read more about parallels with wholly Japanese therapeutic approaches, see more by clicking here.

What theory is ACT based upon?

Relational Frame Theory

Relational Frame Theory (RFT) refers to a research program that seeks to understand the link between human language and cognition. Many of the core concepts proposed in ACT are based on or can be seen from the perspective of RFT. The starting point is that humans think ‘relationally’ and in an arbitrary fashion. RFT argues that the ability to create links between concepts, words and images is the basis of learning, communication and cognition. According to RFT, verbal humans, unlike other animals, are able to link neutral stimuli. A neutral stimulus (in contrast to a conditioned stimulus) is one that was not explicitly learnt and thus does not predict an outcome to psychologically important events. Some examples are:

- If a child is told the word “chocolate” immediately after eating it, the next time the word “chocolate” is mentioned, the child would be able to relate the word to the actual chocolate or that they would be given one even though the word never predicted the actual object during learning.

- If the same child is now told that the word “snack” is another word for “chocolate”, relational frames enable the child to think about the word “chocolate” and even the actual object or the act of eating it even though the word snack did not predict chocolate during learning.

- If the word “dinner” is used prior, during, and post eating their meal, a child is able to link the word dinner to the action of eating. Now if the child was told that the word “supper” is another word for “dinner”, relational frames enable the child to make a connection that the new word refers to the word “dinner” and even think about eating even though the word “supper” never predicted the action of eating during learning.

These patterns of cognition are caused by relational frames or otherwise also known as ‘arbitrarily applicable relational responding.’ These responses are usually informed by contextual cues and/or social conventions more than actual relative properties of the two objects. Some examples of relational frames are:

- Frames of Coordination : “same as”, “like”, “similar”

- Temporal and Causal Frames : “before/after” , “if/then”

- Comparative and Evaluative Frames : “better than”, bigger than”, “faster than”

- Deictic Frames : “I/you”, “here/there”

- Spatial Frames : “near/far”

Relational frames have the following properties:

- Mutual Entailment:

- If A is equal to B, then B is equal to A

- If Osaka is to the west of Tokyo, then Tokyo is to the east of Osaka

- Combinatorial Entailment:

- If A is related to B and B is related to C, then A and C are also related

- If it rains more in Okinawa than Tokyo and it rains more in Tokyo than Hokkaido, then it rains less in Hokkaido than in Okinawa

- Transformation of Stimulus Functions:

- If A makes a person sad and B equals A, then B will also make a person sad.

- If darkness makes you scared, then going for night diving will also make you scared.

Children often learn to name objects and to identify objects that are named. They may also be asked to answer questions like, “Which cup has more water?” , “Which train is faster?”, or “Which box has more toys?”. Verbal rules such as more/less, better/worst, if/then in language act as cues to relational responding whereby we arbitrarily apply relational frames to other aspects of our cognition.

Imagine a young child who goes on a boat ride and experiences terrible sea sickness. Soon the word “boat” becomes an aversive stimulus. The child later learns that a “ferry” is a type of boat and that is sufficient to produce anxious feelings as thinking of going on a “ferry” elicits memories and experiences of going on a “boat. An anxiety trigger can be a neutral stimulus that is arbitrarily linked to a word, thought, emotion, memory or sensation that originally produced anxiety. For instance, the food you ate on the day your pet passed away can trigger feelings of sadness in an arbitrary fashion.

How does RFT explain the principles of ACT?

RFT can explain experiential avoidance, cognitive fusion, and the dangers of suppression. Experiential avoidance and avoidance based techniques such as thought and feeling suppression have been found to predict negative behavioral outcomes. According to RFT, relational networks can trigger pain through a multitude of cues and situational solutions often fail to yield success. Failure to control pain leads to avoidance behaviors. However in doing so, one would cue the avoided event because the underlying relational frame is being reinforced (don’t think of “A” serves as a contextual cue for A). You are more likely to be distressed by the thought, “I am not a fun person” by suppressing thinking about it even though suppressing it might be thought to bring relief. You may also decide to avoid attending a social event even though you value social interactions. This relief is usually short term. The negative behavioral outcome is that you continue to avoid social events and this is reinforced by experiential avoidance and the short term relief it provides. Cognitive fusion according to RFT refers to the automatic process of deriving stimulus relations. For example, if a combination of actions leads to a desired outcome, one learns that these actions have “solved a problem” or “are right”. Cognitive fusion occurs when stimulus functions derived from relational frames dominate our behavior without awareness. Thoughts function as if they are literal definitions. The thought “I am unpopular” can appear as being unpopular instead of just the thought, “I am unpopular”. The funny comment, “I used to think my mind was my most important organ, until I noticed what was telling me that” perfectly describes how cognitive fusion can mislead us. Behaviors are more likely to be determined by verbal rules and evaluations as a result, instead of being based on sensory cues in the here and now. Thoughts and feelings are experiences much like the experience of warmness from a fireplace, melody from music, or smoothness from touching cashmere fabric. The environment we live in will increasingly contain stimulus functions derived from relational frames and less so from direct experience. This process is rarely apparent and often unnoticed.

Is ACT right for me?

ACT is a holistic therapy approach and is not designed for specific conditions. It is widely applicable and can be beneficial to people struggling with stress, anxiety, depression, and psychosis and can also help in facilitating behavior change associated with improvement for a number of medical conditions (e.g., health behavior change or illness self-management). The goal of ACT is psychological flexibility instead of symptom reduction. Research suggests that re-engaging in life in a manner that is values-based and increasing acceptance of difficult internal experiences results in symptom reduction (A-Tjak et al., 2014). ACT is beneficial as a treatment modality beyond mental health specific conditions. Aside from one-to-one therapy, ACT can also be implemented in various formats, duration and settings. ACT can be delivered in the form of a 1-day group workshop and has been shown to be successful for patients with a range of medical conditions including diabetes, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis and cardiovascular disease (Dindo, 2015).

How can I experience ACT?

Make an appointment with us at Tokyo Mental Health for an assessment with our internationally qualified multidisciplinary team of professionals, and we can discuss how ACT can help you in conjunction with your current treatment plan or be a new starting point in therapy. As well as psychotherapies like ACT, we offer counseling, psychological testing and psychiatry services both online and in person. Come visit our Tokyo and Okinawa offices. Our professional psychologists, counselors and psychiatrist will design an individualized treatment plan for you. Contact us for a therapy assessment at our Shintomi office.

References

- A-Tjak, J. G., Davis, M. L., Morina, N., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2015). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 84(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365764

- Ackerman, C. E., MA. (2021, November 25). What is Relational Frame Theory? A Psychologist Explains (+PDF). PositivePsychology.Com. https://positivepsychology.com/relational-frame-theory/

- Dindo, L. (2015). One-day acceptance and commitment training workshops in medical populations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 2, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.018

Dindo, L., Recover, A., Marchman, J. N., Turvey, C., & O’Hara, M. W. (2012). One-day behavioral treatment for patients with comorbid depression and migraine: A pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(9), 537–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.007 - Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(04)80013-3

- Hayes, S. C., & Smith, S. (2005). Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life. New Harbinger Publications.

- Stoddard, J., & Myers, L. (2015, February 22). What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy? The Center for Stress & Anxiety Management. https://www.csamsandiego.com/blog/2015/2/21/what-is-acceptance-and-commitment-therapy

- What is Third Wave Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? (2019, June 14). Therapists Raleigh Durham Chapel Hill NC – Third Wave Psychotherapy. https://www.3rdwavetherapy.com/about/what-is-third-wave-cognitive-behavioral-therapy/

- Hayes, S. C., Levin, M. E., Plumb-Vilardaga, J., Villatte, J. L., & Pistorello, J. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behavior therapy, 44(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

beth.2009.08.002