Tokyo Mental Health is here to support you and provide you with the help you need.

Anger can be an intense emotion. It is often an emotion that incites fear when on the receiving end or even when we notice ourselves getting angry. If we take a look at human evolution, we can find a good explanation for why anger can be linked to fear. Anger is triggered by our fight or flight response – it can be seen as a call to action. When we feel threatened by someone or a situation, we might respond with an expression of anger as a way to protect ourselves. Therefore, anger, much like anxiety, is just another feeling in the wide range of human experience, but it can also have very negative effects on our mental wellbeing and our relationship with others.

Anger is often viewed as an emotion we shouldn’t show. Some of us learn from an early age that anger is only OK to express in certain situations, like when someone has deliberately hurt us. It is common to find that people who are angry are often not well liked, and even feared by others, for example, bullies at school. Also, when we feel anger within ourselves it can be unpleasant to experience both physically and mentally. However, anger in itself is not ‘bad’. In fact, there are some cultures where aggression is valued and promoted. So, why is it that we have this very negative view of anger? How can we manage these negative thoughts and feelings around anger?

First of all, we need to understand what anger is because sometimes many of us aren’t even sure if what we’re feeling is actually anger at all. It is important to recognise we all have different upbringings which can influence our relationship with anger: there are families who have frequent conflicts and angry outbursts, and there are other families who might express anger more passively or internally. Secondly, we need to understand why we feel anger. What purpose does anger serve and can it be ‘useful’? Lastly, we need to explore how we can express our anger in a healthy way – a way that does not harm our own interests or harm those close to us. How could we diffuse our angry feelings when things get a bit too heated?

What is anger?

Anger is an emotional response to an external event or to thoughts, memories, images, or feelings we have internally. Events that trigger anger are usually viewed negatively, and seen as having been caused by something or someone with whom we can be angry. Our stress response is activated and we engage in a “fight” response, meaning that in order to protect ourselves from the perceived threat, our body prepares us to take action.

Most of us can recognise when we’re feeling angry by tuning into sensations from our body, such as:

- heart rate increases

- feeling hot/flushed in the face or neck

- clenching or tensed muscles

- sweating

But anger is not just sensations we feel in our bodies, we also experience the emotional affect of anger. For some, anger can feel like a volcano about to erupt – a feeling that can seem to start in your belly and rise up. For others, anger can feel like a slow burn – a pot that is continuously bubbling away until it spills over. The eruption of the volcano or the spilling of the pot can then be seen as our expression of anger. So the experience of anger feels different for each individual and can be expressed in a variety of ways (i.e. behaviours).

With this in mind, we would then want to know how to cope with our anger before it erupts or boils over. But before we can do that, it’s important to understand a little more about what happens to us when anger is triggered. So, let’s take a look at a model of the “angry brain” and how this is thought to affect our experience and the way we express our anger.

Anger in the Brain

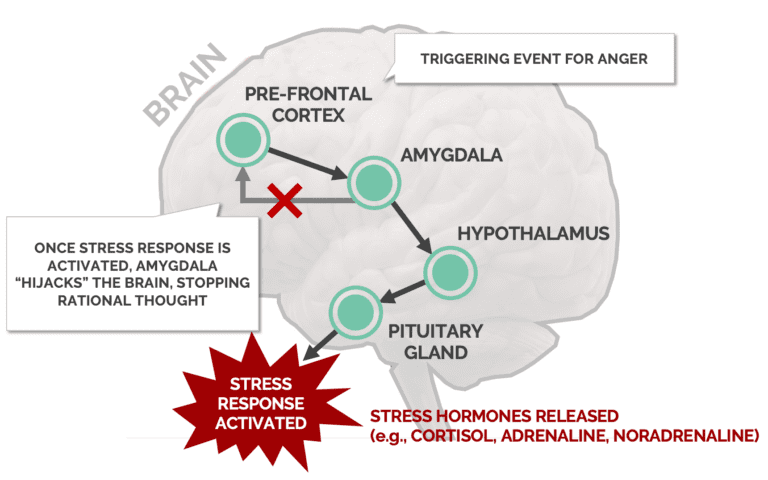

When we feel angry our amygdala is activated. This part of our brain is what some might call “reptilian” as it’s structure is the same as those found in reptiles. It is deeply rooted in our nervous system and has adapted through human evolution to protect us from potential threats using the stress response system. However, humans also have a highly developed part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex and this is thought to be important for the more “rational”, thought-based component of our mental experiences.

During a fit of anger, what happens in our brain is that the amygdala stops signals going to our prefrontal cortex, meaning it does not allow us to think rationally. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘amygdala hi-jack’. So rather than our ‘rational’ thought being in the driver’s seat, the stress response ‘takes the wheel’ and sends signals to other parts of our body. Once this stress response is activated we can respond in a few ways – fight, flight or freeze.

Thinking about the fight response, this could look like expressing anger in a physical way, such as punching, trying to hurt someone, vandalism, or in an intense verbal way, such as shouting, yelling, and screaming.

Considering the flight response, this might look like a need to leave the location you’re in, wanting to cool off, or literally running from the situation.

Lastly, the freeze response, perhaps the least common of the three when thinking about anger, could look like not talking, shutting down or tensing of the muscles (e.g. clenching your fists).

When we consider these varied responses, it is no wonder that sometimes we can be confused about if what we’re feeling is really anger. Additionally, many of these experiences are not pleasant for the person who is angry, nor the recipient of the anger, or even those simply nearby. Perhaps this is why we think about anger in a negative way. Having said this, there must be a reason why humans developed this range of anger responses. Let’s explore how anger could be adaptive and how we might be able to approach anger from a different perspective.

Is it OK to be angry?

As mentioned above, anger is one of many emotions that humans experience. Like all other emotions, there is a reason behind why we feel anger and that is rooted in the stress response. If we look at anger as our brain trying to protect us from danger – then of course feeling angry is OK. Where we all differ, however, is in how we express our anger. So, maybe it is not the emotion itself that is ‘bad’ but rather how we respond to, cope with and express the emotion can be unhelpful and cause us problems.

If we consider how anger works in the brain, as illustrated above, it can seem difficult to stop feeling angry. This is where anger might not be an adaptive response. Anger can often leave us feeling out of control and can then lead to other emotions that are negatively-valued, such as guilt, shame, remorse and regret.

Additionally, let’s think about how anger impacts our relationships. Often we use anger to influence, or even manipulate, other people’s behaviour. For example, if you raise your voice then people might be more likely to listen to you. In this way, we can often associate the feeling of anger with getting what we want. On the individual level, it might feel good to get your own way and have other people adjust to your needs in the short term. However, this way of communicating can have a great impact on your social relationships in the longer term. Furthermore, some of us are socialised not to express any anger. This idea that anger is ‘bad’ is likely to have been passed down through generations and cultures. For this idea to be so prevalent, there has to be a negative social effect caused by the expression of anger. So, perhaps we can conclude that anger is maladaptive if its expression causes the deterioration of social relationships.

On the other hand, anger can be a call to action like all of our other emotions. We can use our anger in adaptive ways to create changes in our social environment. For example, think about all the social movements historically and in recent history that have been motivated by anger. Conversely, if we think about those times when we get angry and feel a call to action, but there is really nothing we can do and no effect we can have, that angry feeling doesn’t seem to go away. Sometimes we might even find ourselves seeking out this angry feeling! Have you ever used social media and gone to a profile or a website that made you just so angry? In these moments we can feel the intensity of anger as if that person was sitting right in front of us and saying those words directly to us. But in reality it’s all online and mediated through a screen; we have nowhere to direct our anger. In this way, anger can be maladaptive because it can call us to action or tell us to be responsive in a situation where it is not always appropriate or where we have little to no power.

Therefore, it might be helpful to reframe how we look at anger. Rather than making a blanket judgement that all anger is bad, let’s look at whether anger is helpful or unhelpful. Next time you find yourself getting angry, think about whether it is helpful to use that call to action i.e. to express your anger, or whether it would be more consistent with who you want to be to step away and take a minute to allow yourself time to assess the situation before acting on how you feel.

Now that we understand more about anger and how it can be helpful or unhelpful, let’s take a closer look at how anger is related to our mental health.

Does anger have anything to do with depression?

In short, yes, it does. Many individuals who have depression report feeling irritable. But what’s the connection? Why would depression and anger go hand in hand?

Many times when we experience pain, physically or emotionally, we can feel quite angry about it. For example, if you stub your toe on a chair as you walk by, you might feel quite angry and think ‘who put that there?!’ You might even push over the chair. But are you really angry with the chair? Probably not. So, if we consider that when we are hurt, in pain, or generally feeling vulnerable, anger might be one response to help us deal with that pain, and more importantly externalise it. However, the angry response described above can illustrate an important issue. Often anger can be a secondary emotion, it can be the way that we express another underlying emotion, such as feeling hurt. For example, have you ever been angry with someone when they lied to you? Sure, anger could be the primary emotion, but maybe underneath that anger you feel betrayed? In this case, anger is the way that you expressed the betrayal and perhaps protected yourself when feeling vulnerable.

The above is analogous to what many people experience with their depression. They are in deep emotional pain and as a result of that they can often externalise and cope with those uncomfortable feelings by getting angry.

Here is a metaphor that can perhaps illustrate this concept. Visualise a cup that can hold all of your emotions in it. For people who are depressed, or feeling a lot of intense emotions, it can be difficult to manage this emotion cup, especially when we experience the ups and downs of life. The cup can overflow or spill very easily because it’s already very full to begin with. When this overflow of emotions happens it can often be expressed as anger, irritability or aggression, because it is generally an easy way to release a large amount of emotional energy, to a point where we can manage it again. That is, until the next time the cup overflows.

What about other mood disorders - does anger have any relation?

Similar to depression, there are many other mood disorders that can leave us feeling very emotionally vulnerable. In order to protect ourselves at these vulnerable times, we might find ourselves lashing out at those around us, finding it easy to express anger rather than feeling other underlying emotions on a daily basis, such as anxiety, fear or hurt. However, it is important to recognise specific mood disorders where forms of anger can actually be part of the diagnostic criteria.

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

DMDD is characterised by chronic, severe persistent irritability (DSM-5). This severe irritability usually presents in two ways: frequent temper outburst, typically in response to frustration, and can be verbal or behavioral; and severe irritability which consists of chronic, persistently irritable angry mood that is present between the severe temper outbursts. Therefore, the expression of anger and frustration is a vital component of this mood disorder.

DMDD is usually found in young children and the onset will often occur before the age of 10. It is generally found to be diagnosed alongside other mood disorders or neurodevelopmental disorders. So, excessive and persistent expressions of anger can be a sign that a child is struggling with their mental health.

Let’s explore more about anger in children and childhood, which might help us to understand the bigger picture about experiences of anger.

Anger in Children

Maybe you are not worried about yourself but about your child who is exhibiting aggressive or excessively irritable behaviour. There might be a few reasons why your child is expressing their anger and doing so in ways that might harm themselves or others.

Typically, our emotions change on a second to second basis. For adults, maybe we have come to understand our thoughts and feelings and can make sense of how our moods change. However, for children, depending on their developmental age, it can be very difficult to process big or complex emotions. Babies and young children are reliant on their caregivers to help regulate their emotions, and this can continue well into early adolescence, especially once you add in puberty and other developmental changes into the mix. Growing up can be a confusing and challenging experience for many children and they might act out in anger to cope with some of these feelings.

For example, toddlers are notorious for throwing ‘temper tantrums’. From an adult perspective, we might think it’s absolutely ridiculous to throw yourself on the floor and cry just because someone told you ‘no’. But if we look at it from a 3 year old perspective, being told ‘no’ can translate to being denied a need. I’m sure many of us have experienced a time when we’ve been ‘hangry’, we get irritable because something might be preventing us from satisfying our hunger. If we apply that same logic to a young child, it would make sense why they become so distressed over seemingly small things. Of course, it is often absolutely necessary to say ‘no’ to kids and put up boundaries for their safety, development and well-being, but kids are often unable to comprehend this and perhaps that is why they react with anger.

What can we do then to help our children to cope with these feelings in more adaptive ways? We can teach them ways to both regulate their emotions, and support them to express how they are thinking and feeling (if they are capable of doing so based on their age and development). One technique that is commonly used for regulation is deep breathing or ‘balloon breaths’.

- It is often a good idea to remove the child from the situation if possible and take them to a quiet place.

- Once in a quiet place, try to make eye contact with them and talk to them in a calm voice – if the child can sense any uncertainty from you then it can add to their concerns.

- Instruct them to take big breaths in and big breaths out, imagining their tummy is like a big balloon.

- You can have them take as many breaths as it takes until they feel ready to talk things through or return to the situation.

By doing this kind of technique, you are providing tools that your child can use when you aren’t around. Additionally, if your child is able to see you modelling emotion regulation, they are more likely to be able to emulate that.

Another way of addressing any expression of emotion with children is to show understanding and listen to them. Even if children are non-verbal and cannot communicate with words about how they are feeling, there are certainly other ways they have to express emotions.

When it comes to expressing emotions, firstly, it is important to ‘label’ our emotions as this can help us and others to understand better. For young children who don’t have the necessary language, it is important that we help them feel understood by helping them label their emotions. So, for example, if you notice that your child is crossing their arms and turning away from you and not listening, this might be a sign that they are angry or frustrated. Just by letting them know, “hey, I can see that you’re angry” is a great way to help them interpret their emotions and for them to feel you are understanding them. Generally, when we feel understood by others, we are more willing to express ourselves and be open to conversation. If another person isn’t listening and doesn’t understand us, that can make us feel bad and lead to a spiral of negative thoughts and feelings. So, when we are trying to assist children with their emotions, step one is usually to name the emotion and show understanding, and step two would be finding ways to address their needs.

I think my anger needs managing. What should I do?

There are several ways to manage anger. However, before we can consider what actions to take, it is important to understand what our anger experience is like. Try asking yourself these questions:

- What makes me angry?

- Are there any situations that particularly make me feel angry?

- What signs tell me that I am angry? (think about the physical symptoms of anger)

- How do I express my anger?

- What am I feeling underneath the anger?

- Am I tired? Am I hungry? Is there another mood or feeling that is influencing my angry reaction?

Once you have an understanding of exactly how you experience anger, it can be easier to apply interventions. If we can be aware of our experiences, then we are more likely to be able to take action, whether that is preventive or proactive. So, let’s take a look at some of the ways we can cope with our emotional experiences.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a technique that is becoming more and more popular in conversations about mental health. It is a practice that incorporates breathing techniques, self-awareness, acceptance, and sometimes guided imagery. Being in a state of mindfulness, means being aware of our experience in the here and now. It also means we do not judge or pay too much attention to our thoughts and feelings, we allow them to be and experience them as they come. If we apply this to anger, it can be a way of noticing our angry feelings and can give us a chance to take action before we end up exploding or boiling over. It can also be a way to defuse anger in itself – sometimes just noticing and feeling our emotions can be enough.

Compassion

Anger can be associated with shame and guilt. We often regret when we get angry and can even turn the anger on ourselves. What can help with reducing these feelings is having self-compassion. By having self-compassion and not being critical to ourselves, we can reduce the amount of negative feelings we have overall.

One way to start fostering self-compassion is to imagine a friend in front of you. Next time you’re beating yourself up about feeling angry, ask yourself: “What would I say if it was my friend?” Try telling yourself exactly what you would say to your friend – see if it makes a difference in how you feel about yourself.

We often are our own worst critics and these self-criticisms lead to more negative thoughts and feelings – if we can show ourselves the same kindness we afford to others, perhaps that will change how we see ourselves and our experiences.

Therapeutic Interventions

Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT)

EFT does what it says on the tin, it focuses on emotions in therapy and will often go into the underlying causes of our experiences. EFT theorises that we learn that expressing anger can sometimes help us to avoid negative consequences or can sometimes help us get what we want from an experience. For example, anger directed towards others could help us to avoid facing our underlying feelings of hurt, shame or regret. EFT also suggests that anger can be focused internally towards ourselves and can take the shape of ‘self-criticism’ or ‘negative self-talk’. This ‘self-hate’ can have negative effects on our self-esteem, which might result in seeking validation from others, or not letting others get close to us because we don’t want them to see our ‘bad’ parts. In these examples given above, we can see how our expression of anger, the direction of the anger (internally vs externally) and the result of the anger all play a role in our relationship with our self and our relationship with others. So, EFT can help us to identify patterns. Additionally, EFT is a great approach to use in couples’ therapy because it can highlight how these patterns appear in our relationships.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (“ACT”)

ACT is an approach that aims to empower clients to take positive action towards the direction of their goals. It is founded on the idea of accepting our thoughts and feelings as they are and using this awareness to inform our behaviour. ACT combines mindfulness with a cognitive behavioral approach. In terms of anger, ACT can help us to identify our triggers, accept our feelings and act differently. A key part of ACT theory is regarding “thought defusion” – this means that we accept our thoughts are just words and don’t instinctively believe them or attach ourselves to them. By defusing our thoughts, we can take a step back and evaluate a situation with a clearer mind. This could certainly be useful when thinking about managing anger.

Tokyo Mental Health can help you manage your anger

At Tokyo Mental Health, we have a variety of therapists who are trained in different approaches such as:

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Emotion-focused Therapy

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

If you are looking for help for your child, we offer both individual and family therapy services. Additionally, if you are concerned about your child’s anger in relation to neurodevelopmental difficulties, we also offer psychological testing for ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorder. These services can help to identify underlying causes for your child’s anger and give you and your child tools for ways to express anger that are more adaptive.

If your anger is affecting your relationship we also offer couples therapy which can help to manage conflict in the relationship as well as individual anger responses.

We also have bilingual therapists who can offer services in Japanese, Spanish or Mandarin so please let us know if you have any preferences when contacting us.

If you are unsure about what the best approach is for you or your child, please contact us at Tokyo Mental Health and we’ll be happy to assist you.

References

- Berkowitz, L., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2004). Toward an understanding of the determinants of anger. Emotion, 4(2), 107.

- Hayes, H. (2020). Understanding Anger. Retrieved 2 June 2021, from https://www.heatherhayes.com/understanding-anger/#_ftn1

- Samad, Dr. A (2018). Anger Effects on Brain & Body. Retrieved 3 July 2021, from https://www.drabdulsamad.com/anger-effects-brain-body/

- Five Secrets to a Stress-Proof Brain (the amygdala hijack). (2019). Retrieved 3 July 2021, from http://beautyecology.com/blog/2019/9/five-secrets-to-a-stress-proof-brain-re-framing-the-amygdala-hijack

- Estroff Marano, H. (2003). Controlling Anger. Retrieved 3 July 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/articles/200311/controlling-anger

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Anxiety disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm05

- Neff, K. (2015). Definition and Three Elements of Self Compassion. Retrieved 3 July 2021, from https://self-compassion.org/the-three-elements-of-self-compassion-2/

- Pascual-Leone, A., Gilles, P., Singh, T., & Andreescu, C. A. (2013). Problem anger in psychotherapy: An emotion-focused perspective on hate, rage, and rejecting anger. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 43(2), 83-92.

- Harris, R. (2011). The Happiness Trap: Stop Struggling, Start Living.

- Davies, W. (2016). Overcoming anger and irritability: A self-help guide using cognitive behavioural techniques. Hachette UK.