- 2023/07/11

- Health Conditions

Have you ever wondered if it is possible to recover fully from a traumatic event?

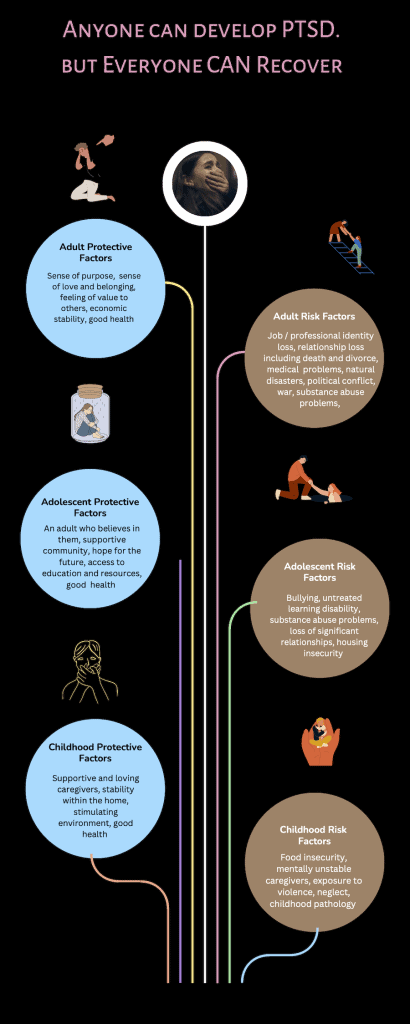

Many people have heard of the condition called PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) and understandably think that it is a lifelong, debilitating condition. After all, that is often how the condition is portrayed in the media: a person who is a shell of who they used to be, angry, alone, and sometimes violent. The reality as observed in the clinical communities is different, as we now know that recovery is possible with a variety of combined approaches. Research has shown that there are some proactive factors and risk factors that may contribute to how a person fairs after surviving a harrowing event. Sometimes, individuals who may appear to have access to every comfort can be the hardest hit after trauma emotionally, while others who seem to have nothing but bad luck are sometimes, rather surprisingly, less affected. However, it is worth noting that the pre-traumatic environment is not the whole story on who fares well or not after trauma: significant recovery often occurs after working with trained professionals who are skilled at providing interventions designed to address the symptoms of traumatic stress. These compassionate interventions are an important component of bringing about real, long lasting, and restorative change.

What is one of the best treatments currently available for PTSD?

One such intervention has decades of support, and is called Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE). Developed by Dr. Edna Foa (1.) her protocols have been studied since the late 1980s, and continue to perform well in trauma-afflicted populations worldwide.

To appreciate the design of PE, the core symptoms that make up the diagnosis of PTSD should be reviewed. The main symptoms break down into 5 categories (2.):

Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways:

- Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s).

- Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others.

- Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend.

- Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s)

Plus:

Presence of 1 (or more) of the following intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred

- Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).

- Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or affect of the dream are related to the traumatic event(s).

- Dissociative reactions (e.g., flashbacks) in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring.

- Intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolise or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).

- Marked physiological reactions to internal or external cues that symbolise or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).

Plus:

Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by one or both of the following:

Avoidance of or efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).

- Avoidance of or efforts to avoid external reminders

- Negative alterations in cognitions and mood

- Inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event(s) (typically due to dissociative amnesia, and not to other factors such as head injury, alcohol, or drugs).

Plus:

Persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs or expectations about oneself, others, or the world:

- Persistent, distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event(s) that lead the individual to blame himself/herself or others.

- Persistent negative emotional state (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame).

- Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities.

- Feelings of detachment or estrangement from others.

- Persistent inability to experience positive emotions (e.g., inability to experience happiness, satisfaction, or loving feelings).

And lastly:

Marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by 2 (or more) of the following

- Irritable behaviour and angry outbursts (with little or no provocation), typically expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects.

- Reckless or self-destructive behaviour.

- Hypervigilance.

- Exaggerated startle response.

- Problems with concentration.

- Sleep disturbance (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep).

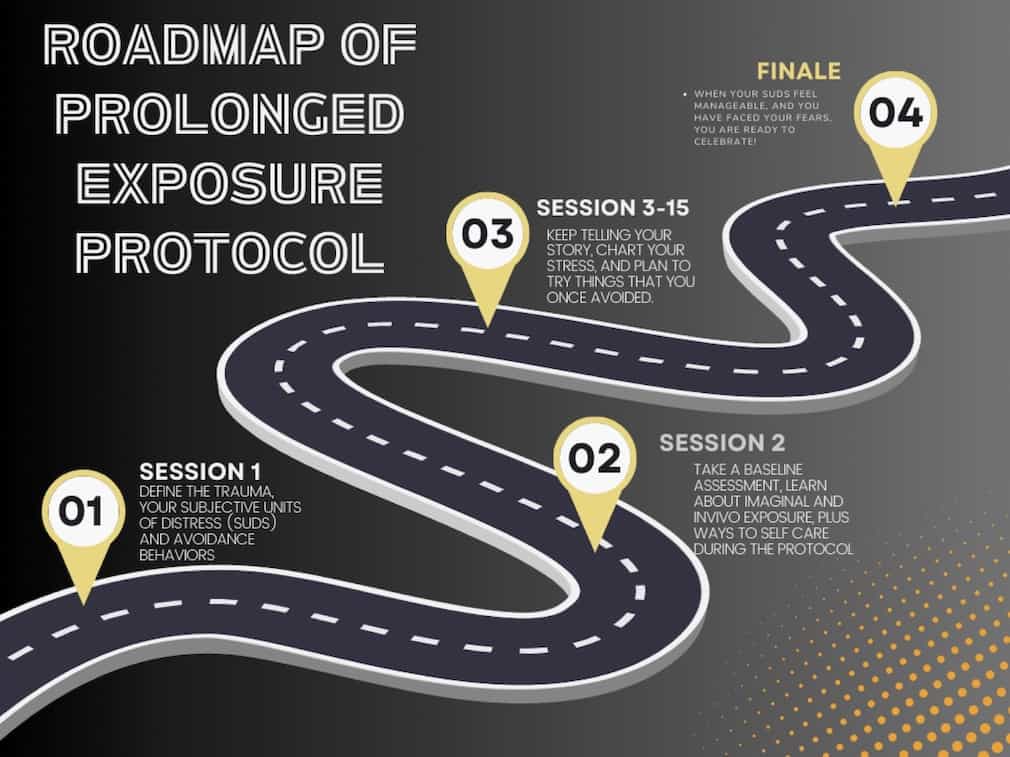

Dr. Foa created interventions specifically designed to destabilise the maladaptive behaviours, thoughts, and emotions associated with trauma. Her protocol can be as short as 4 sessions, or as long as 14-16 sessions depending on the needs of the person. Regardless of the amount of time spent in PE, each session compassionately teaches clients how to fearlessly address the trauma using both imaginal exposure and in-vivo exposure, in a stepwise fashion tailored to the needs of the client.

What would this look like in the real world?

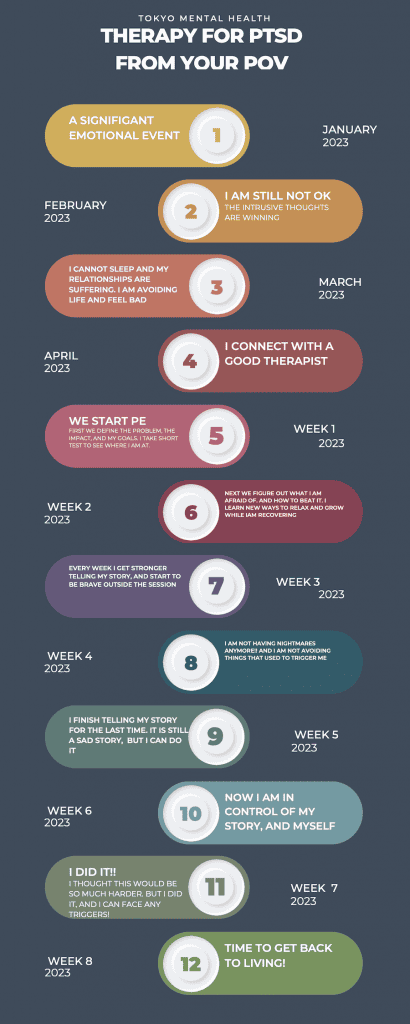

For example, if a survivor of a train accident was traumatised, one could imagine commuting to work would be significantly challenging if they had to use trains every day. This person may start missing work out of a fear of trains, they could have nightmares about the accident, stop seeing friends that lived far away, feeling really anxious at the sound of trains crossing nearby, all the while feeling ashamed of their fear. In a short period of time, this person might face serious consequences at their job, lose contact with loved ones, and turn to methods that are unhealthy to cope with their stress.

If this client were to request PE, the first thing they would do is learn ways to experience safety and calmness before going through their story. Once calm, the person is invited to share only the basic facts about the event, such as the date and time, how long they were in crisis, and when they feel the traumatic event ended. After the first session, the client would be encouraged to employ the calming techniques as they review their basic narrative before the next session.

At session two, the client learns all about their symptoms- with extra doses of reassurance they are not crazy, weak, or any number of things people tell themselves when they are suffering. They would take a baseline assessment of how distressed they are, be taught about imaginal exposure, and collaboratively create a hierarchy of real life experiences that they would find the difficult to face again. Lastly, the client is then taught how to rate their subjective units of distress on a 0-100 scale so they can communicate with their therapist how they are feeling as they work through their narrative.

The third session puts all these together; the client rates their distress, works through their narrative, and engages in calming techniques before and after the verbalization. Then they pick out which of the events on their hierarchy they feel brave enough to face that following week. Any effort this person makes to face their fear is celebrated at the next session, and they work through the narrative again. Each week, this person might find that their distress gradually reduces, and their courage to face parts of their traumatic event are no longer so scary. Depending on the person, this can be a very fast process (i.e about a month), but for others they may find that additional concerns come up that need to be addressed. Keeping with the train example, this person may have developed a lot of anger towards the train company, or feels generally unsafe in the world beyond their control. Each of these thoughts matter, and they are addressed compassionately and with support.

What resources are available in Japan if someone thinks they may be struggling with PTSD?

This of course is a very abbreviated version of the protocol, however if you or someone you love is dealing with PTSD, please contact us through our online enquiry form. You may also visit this website to take a preliminary assessment of your own trauma symptoms and discuss your findings with your provider. We provide PE, and many other empirically sound protocols in person as well as over telehealth.

We look forward to serving you.

References:

- Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences – Therapist Guide (2 edn); Edna Foa, Elizabeth A. Hembree, Barbara Olasov Rothbaum, Sheila Rauch. Published: August 2019

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.)